B. 1986 in Sierpc, lives and works in Kurówko and Kraków. Works with film, multimedia installations, and site-specific objects; active as a cultural animator. Rycharski creates public projects in rural space, designed to engage local communities. Between 2005 and 2009, member of an artistic group with Sławomir Shuty. In 2009, the artist decided to return to his home village of Kurówko. Inspired by tales of fantastic creatures that inhabit the nearby forests, he created a mural with a hybrid animal on one of the houses in the village. The project resulted in several dozen paintings popularly known as rural street art.

Rycharski’s artistic practice draws inspiration from the sacral sphere and folk beliefs, as exemplified by the installation Chapel Gallery, which served as a venue for art presentations. In 2012 Rycharski was awarded the title “Culturist of the Year” care of Polish Radio Three. Rycharski is lecturer at the Multimedia Department of the Pedagogical University of Kraków.

Participant in numerous individual and group exhibitions, such as “Making Use: Life in Postartistic Times,” Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, 2016; “Into the Country,” Salt Ulus, Ankara, 2014; “As You Can See: Polish Art Today,” Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, 2014; “Street Art in the Countryside,” Wozownia Art Gallery, Toruń, 2012.

Daniel Rycharski, There’s No Justice without Solidarity, 2016, sculpture

The history of how the work came into being immediately situates it in a sacral context. Created on the bottom of a dried pond—the artist’s temporary studio near his home village—the sculpture replaced an old chapel devoured by a swamp. It combines references to the debate on the current state of the Church community with themes of intimacy and carnality, brought to mind by the form of the work. The worn out bed covered with white bedsheets and pierced by an old grave cross also marks a rewriting of such works as “My Bed” by Tracey Emin and “A Couple” by Leszek Knaflewski through the artist’s own experience.

Rycharski’s work on the sculpture was inspired by his interest in the social problem of solitude, which is commonplace in rural areas. It can be understood both literally—as the lack of a close relation with another human being—but also as solitude within a community—the inability to find one’s place and a lack of acceptance. It is particularly acute in its pertinence to a broadly understood notion of otherness and marginalized queer identities. The theme is highlighted in the title of the work: “There’s No Justice without Solidarity.” A community of faith may become united not by building its identity on exclusion, but by engaging in a historic act of justice that would consist in admitting wrongdoing and ushering in a new period of openness. Apart from a longing for acceptance, the artist also seems to denounce the lack of such acts in contemporary culture.

Rycharski wants his sculpture to function as a votive offering with the intention of change, a monument to a non-existent ritual of unity. The pursued change also involves an act of penance: it is not the sinner that is supposed to confess, but the community which has long rejected groups of the faithful and denied them the status of rightful members. Honest atonement consists not only in a review of one’s deeds and regret, but also in a will to compensate. In this case, the latter should become an act of inclusion and acceptance of the hitherto rejected faithful, which tangibly transforms the identity of the Catholic Church and the community around it.

Rycharski’s sculpture could be recognized as the first example of a Polish monument to contextual theology, which pursues the goal of understanding the truths of faith in the context of the changing world. The work can also be understood as a voice of liberation theology, which vocally calls for a restoration of social justice. Casting light on these aspects of theological thought provides a chance of invigorating the debate on the role of the Church in Poland.

Daniel Rycharski, Footage from the LGBT Pilgrims’ Haven during the World Youth Days, 2016, video

During this year’s World Youth Days, the LGBT Pilgrims’ Haven operated for several days in an area of Cracow. Set up by a grassroots movement, the initiative formed part of an alternative program of activities and discussions that accompanied the official ceremonies. Tapping into a surge of media interest prompted by the visit of the Pope, the Haven caught the attention of news outlets worldwide.

Such a gesture—akin to a takeover of the official event—performed as an attempt to speak from within the community of pilgrims (together, but still apart) and is recognized in the artistic field as characteristic of a high coefficient of art. Yet at the heart of the project was a need to create a space for a group of people who share a sense of common faith and the desire to propagate it.

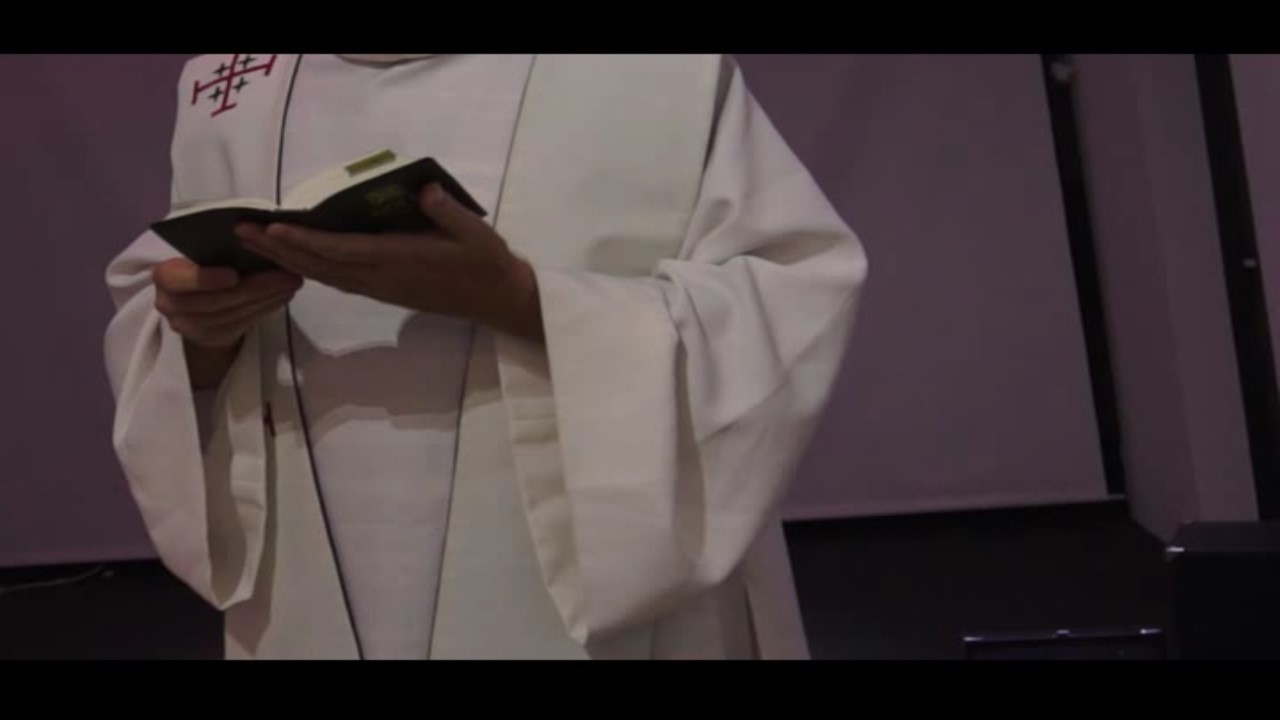

The footage shows a fragment of a Holy Mass, immersed in secrecy, organized at the aforementioned Haven. A multinational community becomes united by the energy of a joint prayer. The camera mostly shows the feet of the gathered faithful in an attempt to avoid portraying people’s faces—when it does happen, the faces are masked and covered. Rycharski’s footage reveals a tension between the overt and the hidden; the tension between the lack of social acceptance of an inclusive understanding of faith and the friendly interest of the media.

The situation animated by the movement Faith and Rainbow serves as an example of reinterpretation work in the spirit of contextual theology. Such activities, underpinned by a willingness to become part of the community of faithful, are pursued as attempts at a tangible change of the Church and its approach to the acceptance of otherness.

Daniel Rycharski, St. Expeditus, 2016, banner / St. Expeditus (rainbow version), 2016, print on fabric

The idea to create a banner with an image of the Christian martyr from the era of the Roman Empire originated from a series of protests known as the so-called “Green Town.” Last year, for 129 days a group of farmers occupied the site in front of the Chancellery of the Prime Minister in Warsaw in a makeshift protest camp, which served as a spatial emanation of a conservative revolution.

Assuming the role of an artist-ethnographer, Daniel Rycharski took many days to observe the situation, engaging in a plethora of conversations and art practices. His activities led to an official request issued by a unit of the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union of Individual Farmers “Solidarity” regarding the production of a banner that would serve both as a trade union identification and a tool of protest should such a need emerge.

The resulting “St. Expeditus Banner” is not only an attempt to modernize dated iconography, but also a politically charged image, which builds a community identity on the basis of visions of fortitude and courage derived from the Catholic imaginary. The commissioners of the banner wanted it to revive the forces of the spirit, while the represented saint is intended to offer support in hopeless matters. The original banner was officially handed over to the farmers in May 2016 in Warsaw.

For a similar reason—the need of support in a difficult cause—the banner also became one of the symbols of the movement Faith and Rainbow—an informal organization that gathers members of the LGBTIQ community marginalized by the Church. Dedicated to that community, various forms of the composition in its rainbow version have graced the movement’s events on several occasions. Also in this case, the strong appeal of the image (self-portrait of the artist who partly identifies with both communities) can be used as a symbol of common identity.

The fact that one motif created by the artist was adopted by two different communities reveals a search for symbols vested with a unifying power. It is also an interesting example of visual awareness—an attempt to develop a visual language with reference to the broadly understood realist idiom, especially popular in contemporary religious art. This work proves how a seemingly conservative form may acquire a political edge through the context of its use.